“The current emphasis on oral approaches to scripture engagement is, generally speaking, a laudable development. Since oral communication is indeed the primary means of communication for many people in the South, it is indeed natural and important to recognize the importance of oral approaches. However, this development also raises a number of questions that need to be addressed, especially in relation to Bible translation.”

Dick Kroneman, SIL International Translation Coordinator, asks the following questions:

- How do we define the concepts of literacy and orality? To what degree are they distinct, and to what degree do they have overlap?

- What is the relation between orality and literacy? Are they in competition with one another? Or, should they rather be viewed as being complementary?

- What can be said about the relationship between orality and literacy from a biblical theological perspective?

- What can be said about the relation between orality and literacy from a historical perspective?

- What could be done or should be done in order to keep a balance between orality and literacy in Bible translation and scripture engagement projects?

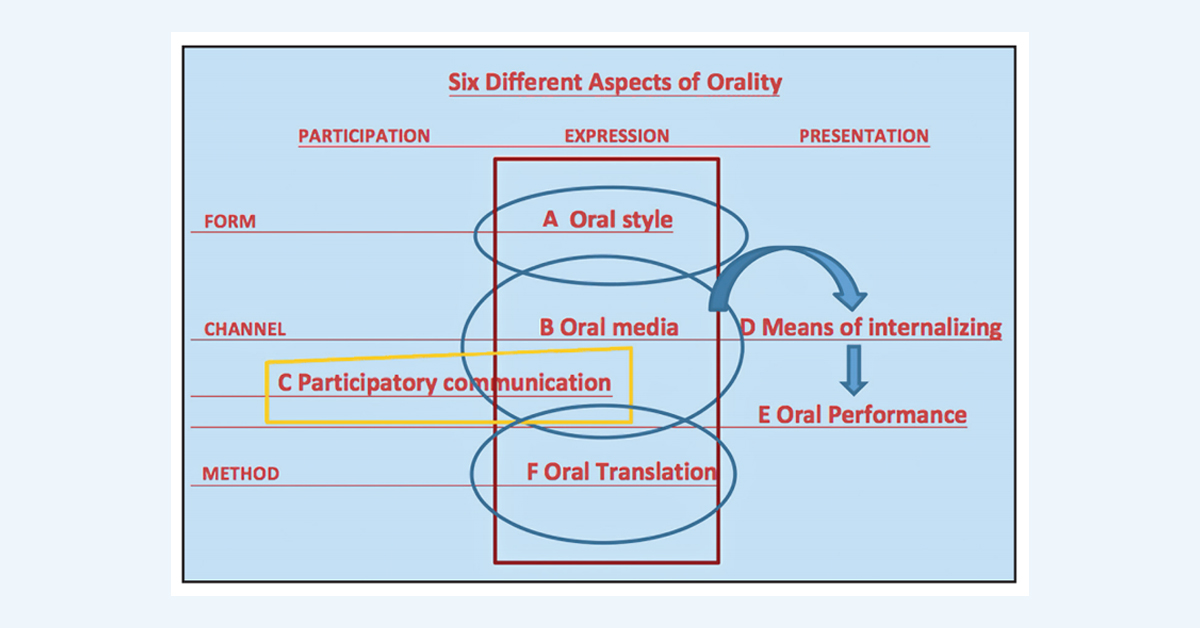

Six aspects of orality are identified:

- A. Orality as a style of communication, which may also occur in print media

- B. Orality as a mode of communication (as opposed to print communication)

- C. Orality as a form of interactive, participatory communication

- D. Orality as a means for internalizing a story that is to be shared with others

- E. Orality as performance

- F. Orality as a method of translation and translation checking

Both oral communication and print-based communication have their own strengths. Oral communication is direct, faceto-face communication, which helps us to connect at an interpersonal and emotional level. As a result, spoken discourse often has a bigger impact on the audience than a book, an article, or another form of print-based communication might have.

Written communication, on the other hand, helps to preserve, validate, authorize, and/or amplify a message. Printbased communication also allows readers to digest the communication at their own pace, fast or slow. They can either read in linear fashion, or in non-linear fashion. They can skim the text, while they skip, fast forward, and/or back-track, according to their particular focus during the reading process.